Day of the Dead and the Magical Touch of Chiapas

Content

They highlight our work

Unique trips in Mexico.

Tailor made for you.

Request your tripTailor made for you.

Let a local guide help you plan your trip to Mexico

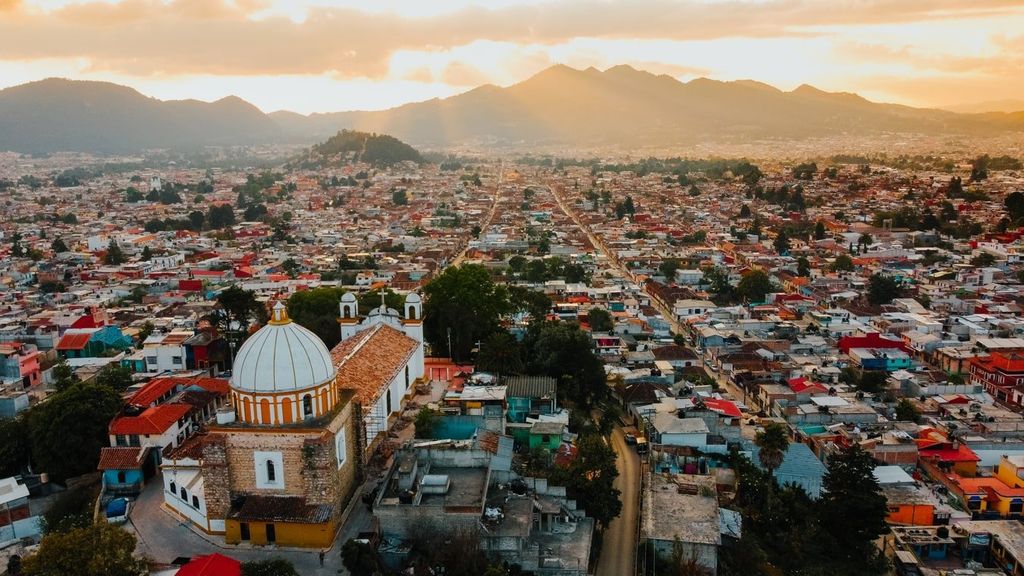

Start tailor-made tripCulture, tradition, diversity, nature, and freshness are just some of the many elements that create the atmosphere of the colonial city of San Cristóbal de las Casas, located among the mountains in the state of Chiapas, in southern Mexico.

With countless fascinating sites, this destination is among the country’s top spots for national and international visitors, and if there is one date to highlight for its brilliant and colorful celebration, it is the “Day of the Dead.” In this colonial city, indigenous customs remain alive; the streets fill with color, tradition, gastronomy, and people who nostalgically remember the physical presence of their loved ones and honor their momentary return.

Day of the Dead since Pre-Hispanic Times

The ethnic groups that make up its current culture already honored the dead during pre-Hispanic times. Mayas, Zoques, and Chiapanecas worshipped death, although in their particular worldview “Death” did not exist; they used concepts of temporary sleep or “little death” and eternal sleep or “great death.”

The Zoques, who call themselves ó de püt (people of the word), are one of the native peoples of Chiapas and still maintain a traditional organization based on a system of duties and stewardship. Their altars are adorned with typical offerings such as flowers, food, and drinks native to the region. Each altar is a gift from the family to all its deceased members; these are decorated with tissue paper in white and purple and have three levels. At the top is the somé, a pavilion with hanging fruits symbolizing the entrance to the underworld. On the second level are the portraits of deceased family members, accompanied by a cross representing the sacrifice and suffering of the Son of God; on the third level are all the foods and drinks that the deceased enjoyed in life. Candles, Mulibé flowers (Cempasúchil), and velvet flowers are spread throughout the altar, symbolizing the passage from life to death.

Day of the Dead Altars

On the altars, the three levels represent heaven, limbo, and earth, although in some villages, such as San Juan Chamula, these are said to symbolize the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Four candles are placed at the foot of the altar, representing each cardinal point.

The light illuminates the souls’ path to the beyond, for their eternal rest. For each deceased family member, white candles are lit—large ones for adults and smaller ones for children and young people. On November 1st, the family gathers at dusk to watch over the candles.

A respected altar must have many traditional sweets; the cooks of each family prepare jammani, puxinú, yumí, candied pumpkin, melcocha, and sweet coyol. On November 2nd, it is customary to visit cemeteries; the graves of the deceased are decorated with colors forming crosses on each one; juncia, copal, and candles complement the decoration. Marimba music plays in various parts of the cemeteries. Many Chiapanecos have the custom of eating next to the tomb. By sharing tamales and rich chocolate, families remember their dead.

Children are also part of this great celebration and are often the most enthusiastic. They go out on the streets asking for “little pumpkin,” dressed as contemporary scary characters, singing and shaking cans filled with stones. They visit every house in the neighborhood, where they are welcomed with sweets and sing in chorus: “we are little angels who have come down from heaven, asking for little pumpkin so we can eat.” When they are gifted sweets, the souls shout, “Long live the aunt!” and if not, they shout at the top of their lungs, “Death to the aunt!” Returning home, the grandparents await them, who will tell ghost stories repeatedly, which the children listen to excitedly while eating all their candies.

Join us on this

journey

Plan your trip with usjourney